Remembering the Tansy, the Forgotten Easter Pancake of Centuries Past

Green, herbal, and slightly toxic.

Almost every holiday comes with its own accompanying foodstuff. For Thanksgiving, it is turkey; for Hanukkah, donuts filled with a thick plug of sweetened jelly, or latkes. Many Muslims break their Ramadan fast each day with dates; people in Japan greet the New Year with mochi and soba noodles. Easter treats seem self-evident: chocolate, eggs, chocolate eggs. But for hundreds of years, the English ate something entirely different at Easter: a sweet, herbal concoction—somewhere between a pancake and an omelette—known as a tansy.

Tansies took their name from the herb tanacetum vulgare, which grows wild across the United Kingdom. With yellow flowers the shape of flying saucers, it had various charming nicknames, including bitter buttons, cow bitter, and golden buttons. Recipes for the simplest tansies are short and to the point. Per a “Mrs. Rendle”: “Pound a handful of green tansy in a mortar, add the juice to a pint of batter, and bake it.” As time went on, however, other herbs found their way into the mix. A recipe in the 1588 Good Housewife’s Handbook used the juice of tansy, feverfew, parsley, and violets, mixed with “the yolkes of eight or tenne eggs, and three or four whites, and some vinegar, and put thereto sugar or salt.” It was then fried. Essentially, it was a big, flat, slightly sweet pancake, with a faint greenish tinge.

It’s likely that tansies originally had a medicinal purpose. The herb itself was believed to cure various ailments: One 16th-century medical tract, Treasurie of Health, prescribes it soaked in a pint of wine for “a drinke for them that be hurte or brused,” while another claims that “it is good to dissolve windiness of the stomach and guts, and to kill worms in the belly, expelling them out. It is used also to provoke urine, and to break the stone of the [kidneys].” (Tansy is now known to be slightly poisonous.)

Its appearance on the Medieval Easter table, therefore, makes some sense. Throughout Lent, Christians endured a long, boring diet of lentils and dried fish. Tansies, one early recipe claimed, were “good for the stomach, on account of discussing the Flatulences generated by eating Pulses and Fish during Lent.” In short, they were probably a practical solution to post-Lenten gut squalls. (But tansies had other, year-round medicinal uses: In the early 19th century, physicians told women with “hysteritis” to place a “tansy pancake” against their abdomens to ease uterine pain.)

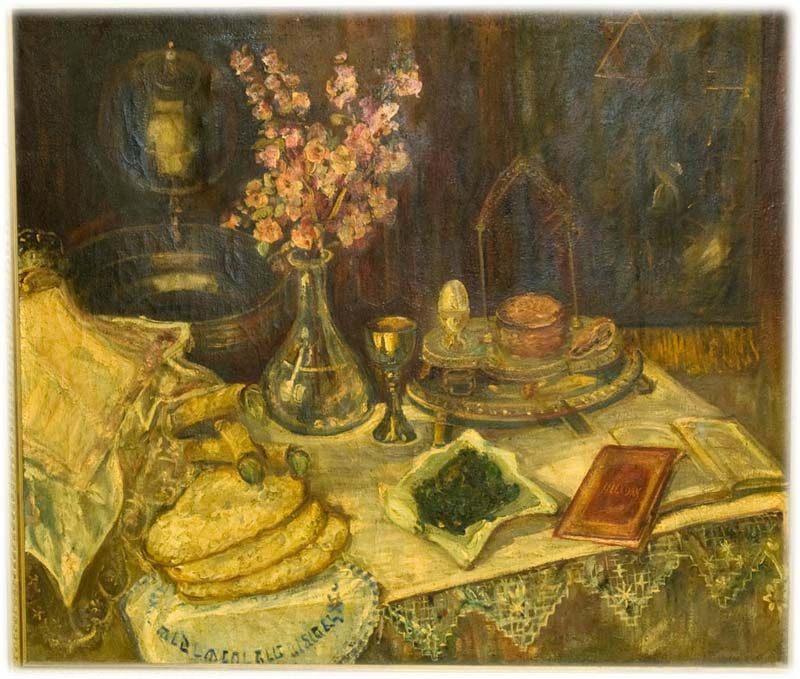

But a curious religious element also seems to have linked the herb with the holiday. Despite commemorating different events, Easter and the Jewish festival of Passover have striking overlap beyond their often-coinciding springtime dates. The word “paschal,” which derives from the Hebrew Pesach, can refer to either holy day. In Italian, Easter is Pasqua; in French, it is Pâques.

For English Christians, eating tansy seems to have been a nod to Easter’s ancient roots—with a strange note of anti-Semitism. In an 1885 Notes and Queries, the scholar Edward Solly traces “the custom of eating tansy pudding and tansy cake at Easter” back to the “the Jewish custom of eating cakes made with bitter herbs.” However, to make it clear that this was still a Christian festival, he wrote, people made a point of eating pork or bacon with the cakes “to take from it any Jewish character.”

Although many Lenten dietary rules were relaxed or forgotten during the Reformation, people continued to eat tansies. Over time, however, they became increasingly decadent. Many omitted the eponymous herb altogether in favor of ingredients such as ground almonds, rose syrup, bread crumbs, grated nutmeg, brandy, artery-choking quantities of cream and butter—and sometimes all at once. Tansies transformed from a kind of herbal pancake into something more reminiscent of a sumptuous clafoutis.

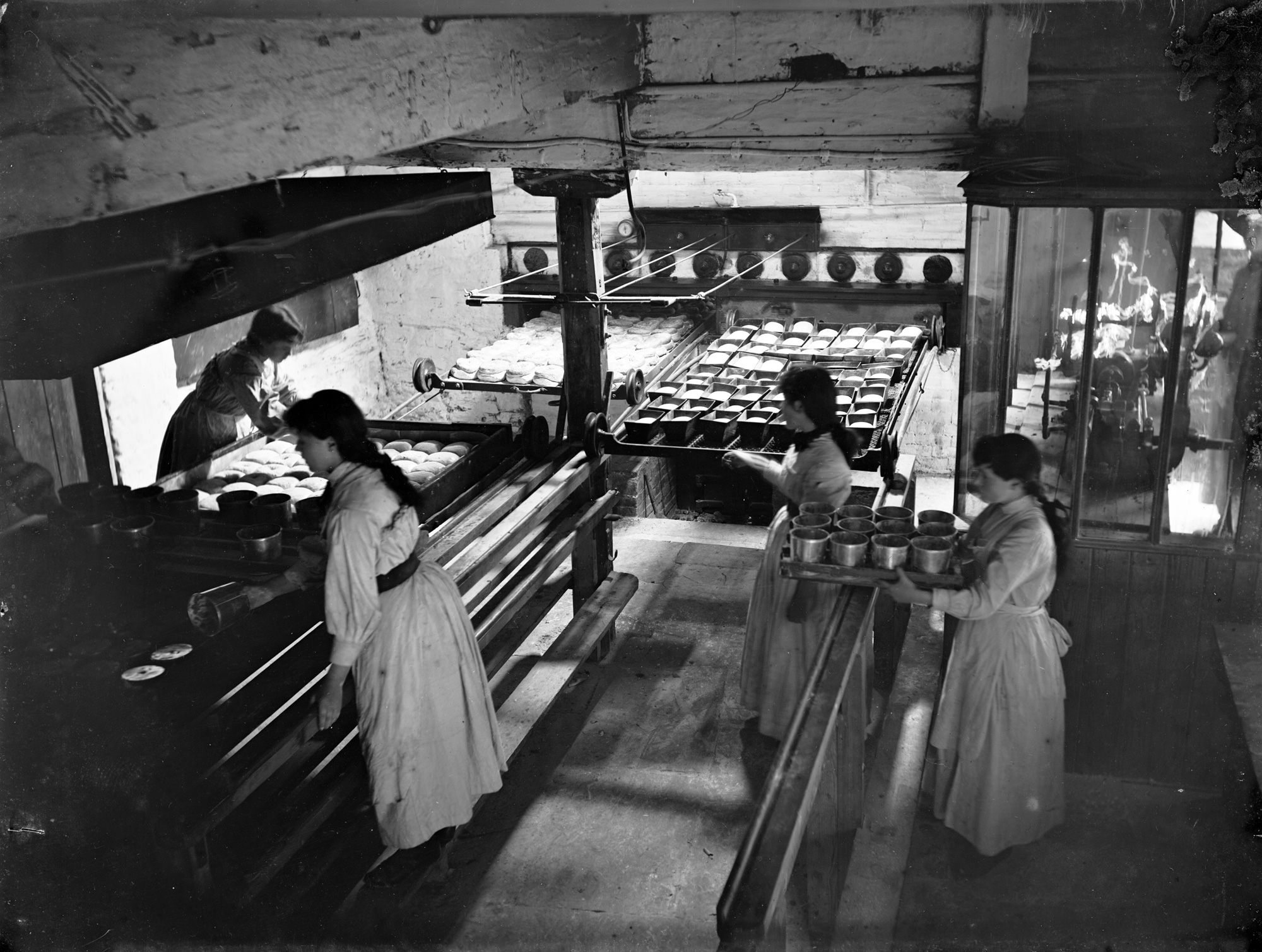

Tansies also played an important role in raucous, regional Easter celebrations. Residents of what is today the northern part of Cumbria would make a “tansy puddin’” on Easter Monday to carry through town to the public bakehouse. A 1905 glossary to the region’s dialect explains: “During the day, women carried flour about and threw it at any one whom they passed. Young men would often steal the puddings or pies from the women. The day ended with a supper and dance.” Held in the church or cathedral, these balls involved “slow, stately dancing, … solemn chanting,” a religious service, and the distribution of tansies with a rich, rum sauce. These were called “tansy neets” or “tansy suppers,” and culminated with young men slipping the fiddler a shilling at the end of the night.

By the early 20th century, however, people were speaking of these puddings and traditions as vestiges of the past. Tansies and tansy neets vanished from Easter plates and celebrations. The Easter Adventurer, from 1826, calls tansy “as essential [to the holiday] as pancake to Shrove Tuesday, furmity to Midlent Sunday, or goose to Michaelmas day.” Today, those holidays and their culinary accompaniments are all but forgotten. And though we celebrate Easter, our chocolate egg hunts and subsequent gluttony would be unrecognizable to any flatulent, flour-throwing, tansy-pinching Easter Monday reveler from centuries past.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook