When Divorce Was Off the Table, English Couples Dissolved Their Marriages With Beer

The practice of “wife-selling” wasn’t legal, but a drink signaled freedom from a relationship that had soured.

On June 2, 1828, inside the George and Dragon pub in Tonbridge, England, John Savage paid George Skinner one shilling and a pot of beer for his wife, Mary. George ordered his beer, and John left with Mary. The pair held hands as they went to start their new life together.

This wasn’t an unusual scene. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, English wives were “sold” for a variety of payments. Prices varied—“as low as a bullpup and a quarter of rum” all the way to “forty [British] pounds and a supper,” the North-Eastern Daily Gazette reported in 1887.

Half a gallon was the total sale price for a 26-year-old known as Mrs. Wells, purchased by a Mr. Clayton in 1876, as reported by The Sheffield Daily Telegraph. Clayton approached Mr. Wells, professed his love for the man’s wife, and asked if he could marry her. Wells shrugged—for the last two years, his wife had lived with Clayton, and he didn’t care what she did anymore. He told Clayton he could have her “for nowt” (or “nothing”), but Clayton insisted he name his price—he did not want her “so cheaply.” Wells countered with a half-gallon (four pints) of beer, and the three of them went off to the pub. After buying Wells his beer, Clayton also offered to adopt the Wells’s daughter—Mrs. Wells was rather attached to her—and when Mr. Wells accepted, Clayton bought him another pint. Mrs. Wells was so pleased with the arrangement that she purchased an additional half gallon of beer, which the three drank together.

“[Wife] sales were located at inns, ratifying pledge cups were quaffed and purchase prices were often in alcohol,” wrote historian Samuel Pyeatt Menefee, in his 1981 book Wives for Sale. “In several cases liquor appears to have played an inordinately large role, often serving as the total purchase price.” In 1832, a sand-carrier named Walter sold his wife at Cranbook Market in Kent for one glass of gin, one pint of beer, and his eight-year-old son; other sales are known to have been brokered with rum, brandy, whisky, cider, a home-cooked dinner, and a Newfoundland dog. When money was involved, it tended not to be very much, even by the standards of the day. In 1825, for instance, a wife in Yorkshire was sold for one pound and one shilling, and one in Somerset for two pounds and five shillings, while a corpse sold to a medical school went for the much higher sum of four pounds and four shillings. (This isn’t to say that the wife was a valueless commodity to be traded, but that the sale was more a formality than a business venture.) Despite these other tenders, beer—by the pint, quart, and gallon—was the most-common currency.

These drink sales had more to do with the lack of divorce options than a bottomless love of booze. In 1857, the U.K. Parliament created the Matrimonial Causes Act, which allowed divorces in certain circumstances. Husbands could be granted a divorce if they had proof of their wife’s infidelity; wives had the added burden of proving incestuous or abusive behavior. Prior to this act, limited as it was, there were even fewer options for ending a marriage in England. You could petition the church or government for a decree, or desert your spouse. Middle-class couples might opt for private separation, which often included a deed stipulating that the ex-husband continue to funnel money to his former wife. Otherwise, desertion often left women impoverished.

Ostensibly, the 1857 Matrimonial Causes Act addressed this problem, but it was still too expensive for the majority of working-class folks. For many unhappy couples, wife-selling was viewed as an easy pathway to divorce, at a time when legally separating was often out of reach. “The practice in England was not really a sale, but rather a sort of customary divorce plus remarriage in which a woman who had committed adultery was divorced by her husband and given to her partner in adultery,” says Matthew H. Sommer, a Department of History Chair at Stanford University and author of Polyandry and Wife-Selling in Qing Dynasty China. Officially divorcing would have cost around £40-60 in an era when nursemaids earned £17 pounds a year. This arrangement benefited all parties—the wife got out of a miserable marriage, her new husband got a partner, and her ex got his buzz on.

At the time, alcohol authorized all kinds of deals. People across many fields—laborers, farmers, agriculture workers, and more—would seal contracts with a handshake and a pint of beer, “to wet the sickle and drink success to the harvest,” Menefee wrote. “In such ritual carousels, the connection of drinks with a change of state and especially with a contract is emphasized.”

Indeed, the process was generally viewed as binding. “The great majority of those who took part in wife-selling seem to have had no doubt that what they did was lawful, and even conferred legal rights and exemptions,” The Law Quarterly Review reported in 1929. “They were far from realizing that their transaction was an utter nullity; still less that it was an actual crime and made them indictable for a conspiracy to bring about an adultery.” (A murky understanding of the rules surrounding wife-selling is a plot point in Thomas Hardy’s 1886 novel The Mayor of Casterbridge: The Life and Death of a Man of Character.)

Twenty-five-year-old Betsy Wardle learned that lesson the hard way. In 1882, her husband sold her to her lover, George Chisnall, for a pint of beer. The pair married, but Betsy was soon charged with bigamy, arrested, and brought to Liverpool Crown Court to stand trial. When Betsy’s landlady, Alice Rosely, took the stand as a witness, she told the judge that she knew of the ale sale, but believed it was legal to house the couple. “Don’t do this again,” Justice Denman warned her. “Men have no right to sell their wives for a quart of beer or for anything else.” He sentenced Betsy to a week of hard labor.

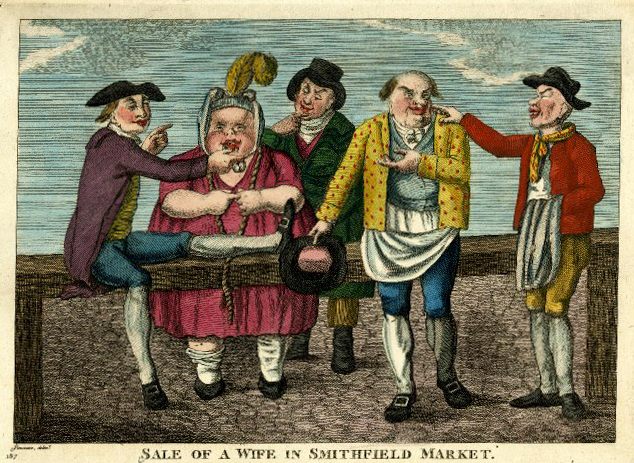

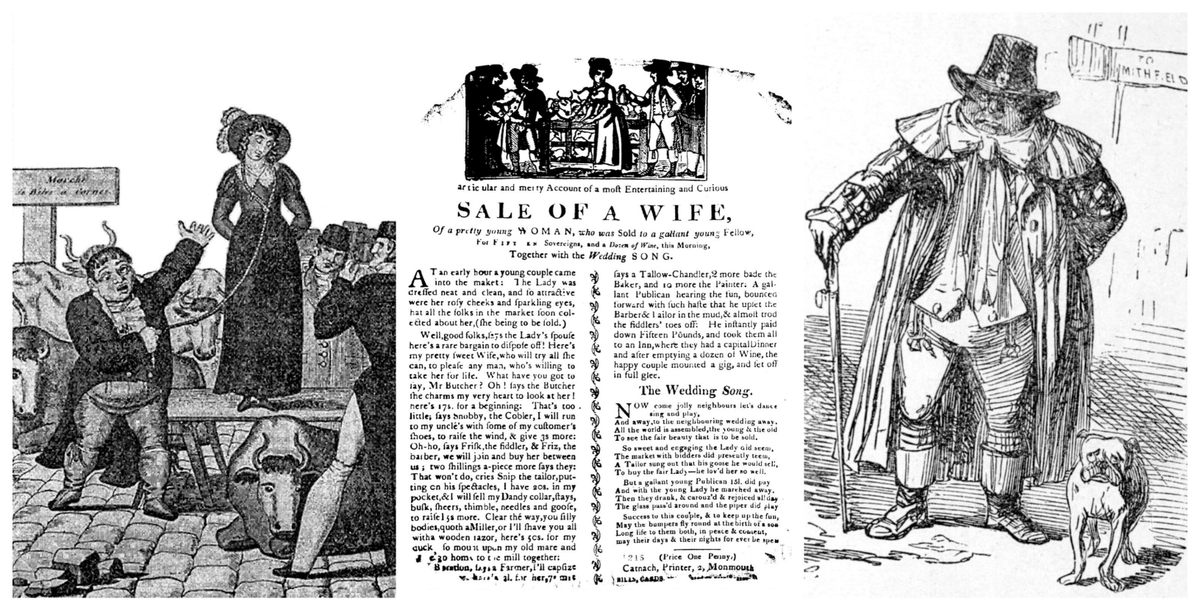

In 2019, it all looks terribly misogynistic. Menefee reported that some sales hinged on complaints about a woman’s barrenness or her “nagging”—suggesting that a man wanted a younger or more submissive partner. Some of the visuals are also especially hard to stomach: In satirical cartoons of the era, husbands were shown to peddle their wives at busy Smithfield Market in London wearing halters—the same way they’d transport livestock—or ribbons that would tie them to their new ‘owner.’ Some of these cartoons were based on real events.

But despite the sexist overtones, women were often on board with the process. In his 1993 book, Customs in Common, historian Edward Thompson indicates that the sales were often approved by the women, reporting that out of 218 wife sales he had analyzed between 1760 and 1880, 40 were cases where women were “sold” to their existing lovers, and only four “sales” were recorded as being non-consensual. He did note that consent was sometimes forced, or the best of a number of unappealing options, as was the case in 1820, when one wife stated that her husband had “ill-treated her so frequently that she was induced to submit to the exposure [of the ritual] to get rid of him.” (However, Thompson added, the wife had lived with the purchaser for two years before the sale.) Writing in the Review of Behavioral Economics in 2014, economics scholar Peter Leeson noted that wives could also veto the buyer. Menefee also notes that many of the purchasers had “more remunerative, socially prestigious positions,” than the sellers, suggesting that upward social mobility may have played a part.

Though many accounts seem to indicate that wife-selling usually worked out fairly well for the women, wives’ voices are rarely heard in the historical accounts, which end around 1905. Most of the narratives are told from men’s perspectives. Of course, it wasn’t a panacea for all of the problems faced by women of the era, married or not—they still faced high-rates of mortality in childbirth, had limited educational offerings, and were expected to defer to men. For those who willingly entered into the sale, though, it may have been a start.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook