Medieval Jews Celebrated Passover With Bird-Human Hybrids

An illuminated manuscript interpreted the prohibition on graven images in a creative way.

In the Judeo-Christian tradition, in the second commandment, God lays down a law: “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image,” that is, don’t make any images or idols to worship. The fifth book of the Old Testament, Deuteronomy, which is thought to have been written later than the other books, gets more specific, by warning against making an image that looks like a man, woman, beast, bird, fish, or “any thing that creeps upon the ground.”

As in many, maybe all, matters of Jewish law, the exact meaning of this rule has been debated for centuries. At times, Jewish leaders (and leaders of other religions) have advised artists to avoid any representation of human figures. At other times this scriptural stricture is interpreted more loosely. But in the early 14th century, it resulted in a remarkable illuminated manuscript that illustrates the story of Exodus without ever showing a human face.

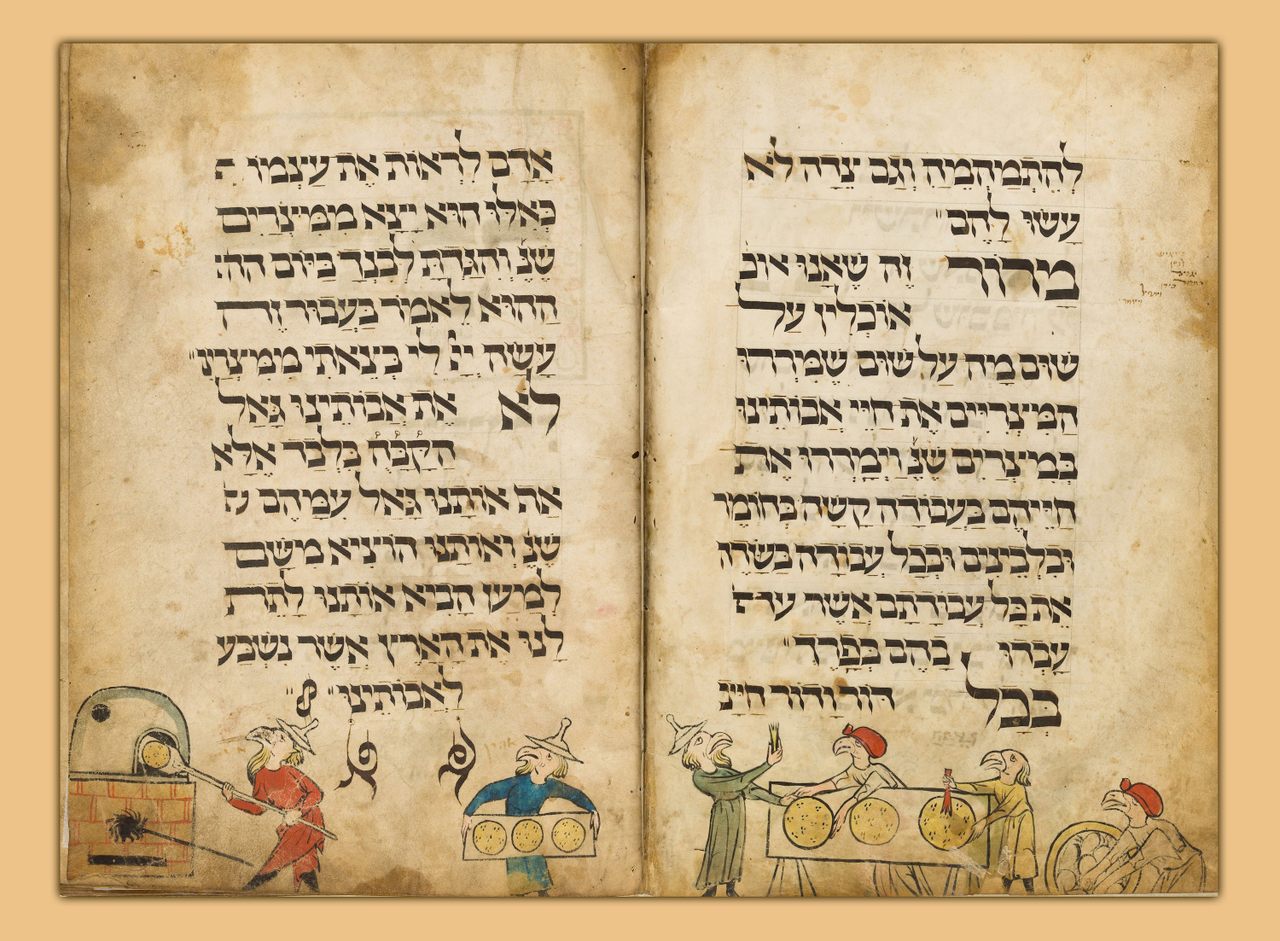

Some of the figures simply have empty circles where their faces would be. But others, the ones representing Jewish characters in particular, have bird-like heads and human bodies. It is “the earliest surviving example of the phenomenon of the obfuscation of the human face,” scholar Marc Michael Epstein writes in his book Skies of Parchment, Seas of Ink: Jewish Illuminated Manuscripts, and it’s a mystery. Why did the artist choose these avian heads? And what do they mean?

“It’s so gloriously weird, and yet it goes so much to the depth of what people thought and felt,” Epstein says in an interview. “The people who created this manuscript were interested in thinking about a metaphor that encompassed the way they expressed themselves as Jews in that time and place.”

Based on the style and other clues, the manuscript can be dated to the early 14th century, from the upper Rhine region of southern Germany. Today it’s held by the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, but little is known about its creation or the patron who commissioned it.

Before the medieval period, the text of the Haggadah, recited on Passover as a retelling of Jewish exodus from Egypt, was often included in larger texts. This is one of the earliest extant examples of a stand-alone Haggadah. Originally 50 pages (47 of which survive), it’s signed by a scribe named Menahem. The beginning and the end of the text feature full-page illustrations, showing a family at a seder table and the rebuilt city of Jerusalem, a reference to the end of the seder, which imagines that it will be celebrated “next year in Jerusalem.” Throughout the text, marginalia show the events of the Exodus story and families observing Passover traditions—following Moses through the Red Sea, performing a hand-washing ritual, making matzo.

None of these figures have human faces. The Egyptian figures, along with the celestial ones, such as angels, the sun, and the moon—have blanks where they’d normally have ears, eyes, noses, and mouths. The Jewish figures all have facial features and large, pointed beaks. Some have pointed ears.

For many years, the manuscript has been called the “Birds’ Head Haggadah,” for obvious reasons. But the ears stand out as even more unusual, and have been a point of contention among scholars. Ruth Mellinkoff, who studied medieval art, identified them as pigs’ ears and argued that the Haggadah’s figures are anti-Semitic representations. (In Jewish tradition, pigs are unclean animals.) But Epstein has a different theory: The ears indicate that the figures are griffins, mythical lion-eagle-human hybrids associated with holiness. The lion had long been a symbol of Jewish strength, and the eagle was a symbol of German imperial power, going back to the reign of Charlemagne. The figures in the Haggadah showed both Jewish identity and their affiliation with local rulership, Epstein posits.

“It would be great if someone was brave enough to refer to it as the ‘Griffins’ Head Haggadah,’” he says.

Although the Haggadah contains the most famous example of these sorts of half-human figures, scholars believe it just happens to be the longest-surviving text of its kind. Most likely there were manuscripts in the 13th century that used this work-around, and the style continued to show up throughout the 14th century in European Jewish art. Around this time, some rabbis advised Jewish people to avoid creating any images of humans or animals. Others suggested that only human faces were out of line. The Haggadah was, in this context, a document that tended toward a freer, more liberal view of religious practice.

But the law against graven images was not always interpreted so strictly. “Jewish avoidance or neglect of visual art has usually been more historically contingent than theologically necessary,” writes Melissa Raphael, a religious scholar at the University of Gloucester. When Jewish communities were thriving in the Middle East during the Islamic Golden Age or in the Byzantine Empire, it was the tastes and ideas of the dominant religions that pushed Jewish artists to avoid depicting people. Before the Middle Ages, Jewish art of certain eras readily depicted people.

The figures of the “Birds’ Head Haggadah,” then, can be seen as a product of the time, place, and culture in which it was made. Many of the Jewish bird-figures wear pointed hats, used in Christian art to distinguish adult Jewish men from Christians. Faced with this sort of discrimination, perhaps the artist created the Haggadah as a way to show the power and unity of the Jewish people.

“The non-Jews, by contrast, are literally blanks—nothings,” writes Epstein. “[They] have become faceless and powerless—erased like the objects of their idolatry.”

This story originally ran on October 24, 2018.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook