Why Monks and Nuns Make So Many Beloved Foods

Tastes like heaven.

In Madrid, Spain, the arrival of December means a proliferation of markets and ferias. There is the main Christmas market on Plaza Mayor, an artisans’ market on Plaza España, and mercadillos, small ferias, throughout the city. But my bullet journal usually bears only one reminder: Expoclausura, Madrid’s annual fair for monastery- and convent-made foods. With a wide selection of marzipan, turrón, polvorones, jam, and other holiday treats, Expoclausura is the place to go to for these celebrated Spanish delicacies. Made by monks and nuns from all over the country, they are known for their simple recipes, high quality, and focus on tradition.

According to Miguel Ángel del Puerto, the founder of Expoclausura, there are a little over 1,000 cloistered monasteries and convents in Spain, and close to 30 percent of them make a traditional food product. But Spanish monks and nuns aren’t unique—their brethren worldwide also veer towards the traditional when it comes to food production. In Germany and Belgium, many monasteries brew beer. In Russia, convents often bake bread and pirozhki, savory and sweet Russian pies. In Greece, monasteries make olive oil, honey, and walnut paste. In France, convents and monasteries produce cheese and wine.

In the competitive world of food and drink, one might expect monks and nuns to struggle. But that doesn’t seem to be the case—at least at the Expoclausura. Most of its stock sells out within the first few days. When I discovered the fair after moving to Madrid, I noticed a jam made by the monks of the Monasterio de Santa Maria de Huerta. Curious about what a mixture of lemon and apple would taste like, I purchased a jar. The next year, when I returned—only one week into the fair—they had already sold almost all of their jams. I made a note in my journal: “November: find out the opening day for Expoclausura and go ON THAT DAY.”

Outside of Spain, the foods of many convents and monasteries find similar, local acclaim. So what makes their products so popular, and why is it that monks and nuns produce so many beloved foods?

I visited Monasterio de Santa Maria de Huerta in search of answers. Located about 200 kilometers northeast of Madrid, the monastery was founded in the 12th century by the Cistercian order. Its complex is a mix of original construction and later additions that combine Roman, Gothic, Plateresque, and Herrerian architecture. Nineteen monks live in the monastery; some hail from as far as Nigeria and Peru. They lead a cloistered lifestyle of prayer, study, work, and limited interaction with the outside world. Work has been an integral feature of the Cistercians’ philosophy for centuries—and the tradition they carry forward when they make their jams.

“Work forms part of our spiritual life,” says Father Diego Romera Fernández. “It [doesn’t] disconnect us—it adds to our life of prayer.” He is one half of the team that heads the monastery’s fábrica, the factory that makes the jam I love. The other half is Brother Antonio Manuel Pérez Camacha.

“In our order, the monks have always lived from the work of their hands,” says Brother Antonio Manuel. “It’s a job with which we maintain ourselves, because for us it is important to lead a way of life like everyone else. Everyone works to live and we do too.” They aren’t alone in their commitment to earning their livelihood—other orders often speak of the importance of working. This dedication, along with the discipline that monks and nuns often exhibit towards their vocation, helps explain the success of their products.

Another reason for that success is their contribution to their local communities. Earnings from the jam production at the Monasterio de Santa Maria de Huerta don’t only go towards the monks’ living expenses. They contribute to the maintenance of the monastery’s old buildings and fund a homeless shelter and alms for the needy.

According to Almudena Villegas, a food historian and member of the Real Academia de Gastronomía, the Royal Gastronomic Academy of Spain, this commitment to helping the poor is one of the major reasons people are drawn to monastic-made foods. Much like the products of companies that use sustainable practices or donate to charity, monk- and nun-made foods have a charitable halo.

The Monastery hasn’t always produced jam. In the 1950s and 60s, they made cookies but couldn’t compete with commercial producers. Later they turned to tending livestock and cultivating the surrounding land. But both the return on their labor and the time demands didn’t fit well with monastic life. “The animals know nothing about hours, dates, or days,” says Brother Antonio Manuel. “They always need to be taken care of. And, besides, to have a good production, one has to have many animals and large expanses of land, and we are a small community.”

To sustain itself, the community switched to jam in the early 1990s. Because they had quince trees, they started by making dulce de membrillo, quince paste. After deciding to expand to other kinds of jams, they sent two monks to learn from the nuns at the Monastery of Our Lady of Los Angeles in Seville, who have been making jams for years. A month-long apprenticeship later, the two came back armed with recipes, skills, and confidence. “If you know how to make one [kind of] jam, you can make them all,” says Brother Antonio Manuel. “It’s simple.” Peach and plum were the first flavors they made: “the traditional tastes,” according to Father Diego.

Access to expertise of their brethren in other religious institutions—as well as to centuries of experience in their own orders—is often a hallmark of monastery and convent production. Another is monks’ and nuns’ natural instincts for local heritage. “[Making of traditional foods] is a reflection of the frequent draw that monks and nuns have to tradition,” says Maria Soledad Gómez Navarro, Professor of Modern History at the University of Córdoba. “They respect [it] greatly and preserve old books with recipes of traditional foods and products on which they relied upon in their monastic [life].” Miguel Ángel agrees: “Convents [and monasteries] continue to live ancient [kind] of life. Their pride is being able to preserve what’s being lost.”

Although the Monastery of Santa Maria de Huerta makes over 35 varieties of jam—some combinations such as kiwi, lemon, and tequila are quite modern—tradition forms an important part of their production. Their recipes are simple: They use only the main ingredients, sugar, and sometimes lemon as a natural source of pectin. There are no preservatives, additives, or artificial colorings in any of their jams. Their labels are designed in-house “by a Brother with artistic talent,” says Brother Antonio Manuel. Most everything is done by hand, and they work in silence.

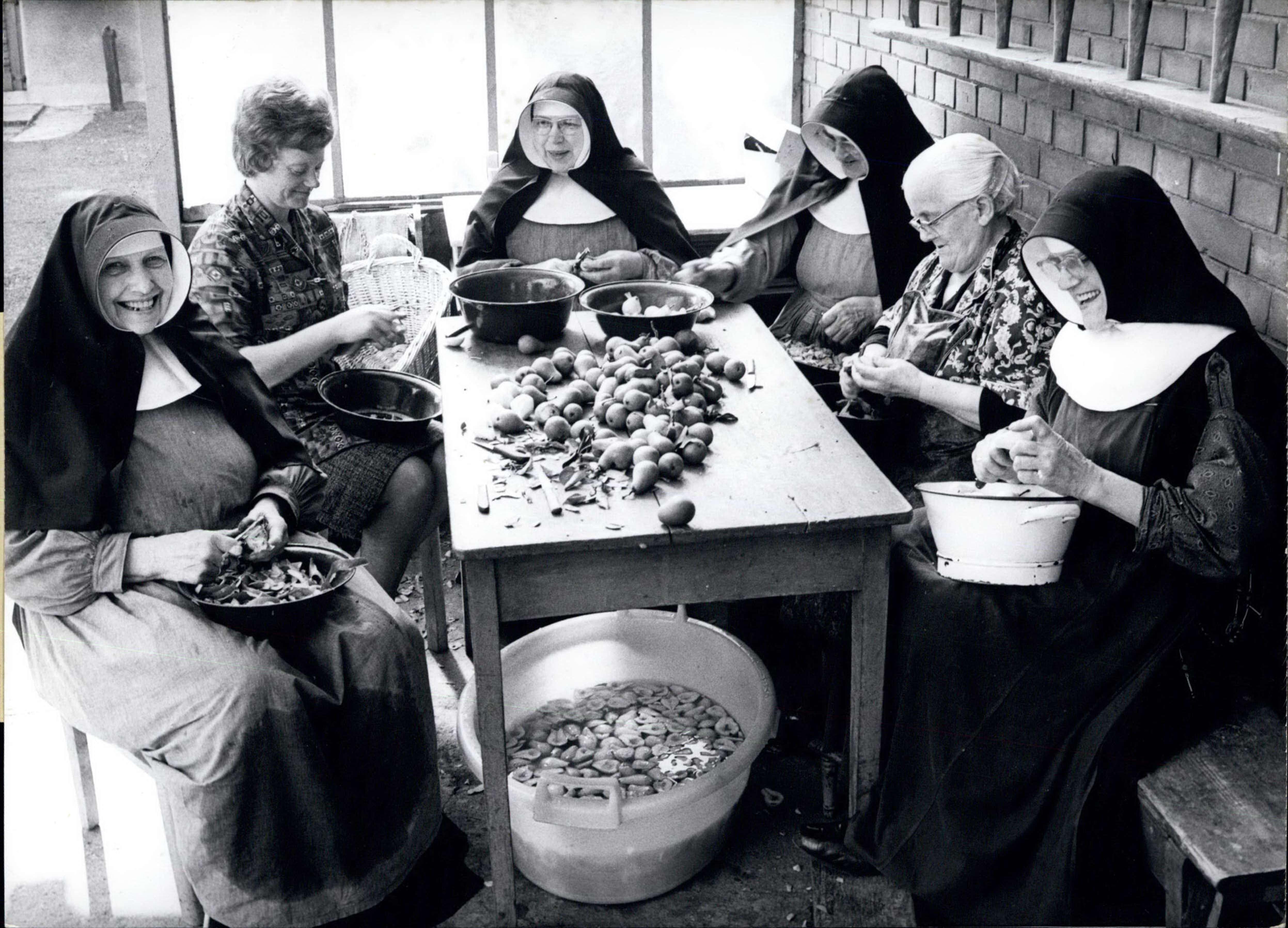

The fábrica is a 17th-century building right behind the main complex of the monastery. Flanked on two sides by fruit trees and a green house, it consists of several rooms in which the monks wash, peel, mash, and cook the fruit. Plums, pears, apples, and quince come from their own trees, while the rest is bought at a local cooperative. Almost all the brothers join the process when production is in full swing. When I visit, they are making dulce de membrillo and labeling jars of peach jam they’ve recently finished preserving.

Despite the fact that they aren’t professional chefs, Father Diego and Brother Antonio Manuel appear at home running the fábrica. Every step of the jam production has been calibrated to assure maximum efficiency, and everyone has a role. Some brothers wash and peel the fruit, others sterilize, fill, and seal the jars, and yet others complete the production by labeling them. The division of duties follows a strict physical-exertion rule: The oldest get the easier task of decorating the jars, while younger monks do the rest.

This effort is almost entirely homespun. Aside from two industrial-type machines—a jar sterilizer and a bain-marie for cooking the fruit—brothers do everything by hand. They show me their supply closet stocked with pots and pans, plastic containers, knives, and peelers. The set up reminds me of my kitchen, although perhaps a little bigger. They’re especially proud of the peelers they recently discovered for tomatoes. “We used to have to boil them,” says Brother Antonio Manuel. “And now we can peel them cold,” adds Father Diego.

The two work well together. They finish each other’s sentences, and they balance one another when it comes to their favorite steps of jam making. While Brother Antonio Manuel prefers to oversee the cooking of the fruit, Father Diego likes sterilizing the sealed jars. “It’s a beautiful moment to see [the jam] come out, to witness the color it has,” he says.

There is another thing they agree on. Although their preserves have been very popular—they stock gourmet stores in both Madrid and Barcelona and participate in several Christmas markets—they don’t want to expand. “It’s a business, but it doesn’t live like a business,” says Brother Antonio Manuel. “We have to control production, because if it gets out of hand, we would not be able [to sustain it]. We would have to be working all day, and that is not our thing. We [didn’t become] monks for that.”

With a small-batch, traditional, handmade product, religious communities such as that of Brother Antonio Manuel and Father Diego fit well into today’s food ethos. “Now people are looking for more home-made things, better quality [things], and [monks] may have an edge because they produce them the old, traditional way,” says Francisco García-Serrano, Professor of History and Director of Ibero-American Studies at the Saint Louis University of Madrid. Another reason for that edge is nostalgia. “People like to buy [those foods] because they remember when they were little how it was when their grandmothers made them, when they lived in villages,” says Miguel Ángel.

The monks of the Monasterio de Santa Maria de Huerta understand that. Yet while always conscious of tradition, they are also looking to improve by either adding varieties or tinkering with old recipes. They’ve recently brought back the carrot jam they haven’t made in years, and they’ve been working to reduce the quantity of sugar in all of their preserves. But, mainly, it’s all about the passion. “The only secret is the interest that things come out well,” says Brother Antonio Manuel. “It takes work,” adds Father Diego. “Work and dedication,” continues Brother Antonio Manuel. “Especially dedication.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook