From a Skull to a Kiss, Atlas Obscura’s Favorite History Stories of 2022

Ancient Egypt, medieval Middle East, and 19th-century America all saw surprising new histories uncovered this year.

The exciting thing about history is that even though it is in the past, it is always changing, as we unearth surprising new clues and ask provocative new questions about the events that shaped our world. These Atlas Obscura stories rediscovered unexpected truths about our shared past, from the overlooked story in King Tut’s Tomb, to the forgotten women who ruled the medieval Middle East, to the 20 seconds of lost film that changed movie history.

How 20 Seconds of Film Changed Movie History

by Line Sidonie Talla Mafotsing, Editorial Fellow

While looking through a box of unidentified film reels in 2017, Dino Everett, a film archivist from the University of Southern California, unfurled a section of film showing a Black couple locked in a romantic embrace. The short, only 20 seconds long, showed the pair kissing, swaying, kissing again, and just smiling at each other. Everett had rediscovered a lost moment in film history: William N. Selig’s 1898 short film Something Good-Negro Kiss, the earliest known depiction of black intimacy on screen. The find went viral, writes Line Sidonie Talle Mafotsing, and is now prompting researchers to rethink the beginnings of Black cinema.

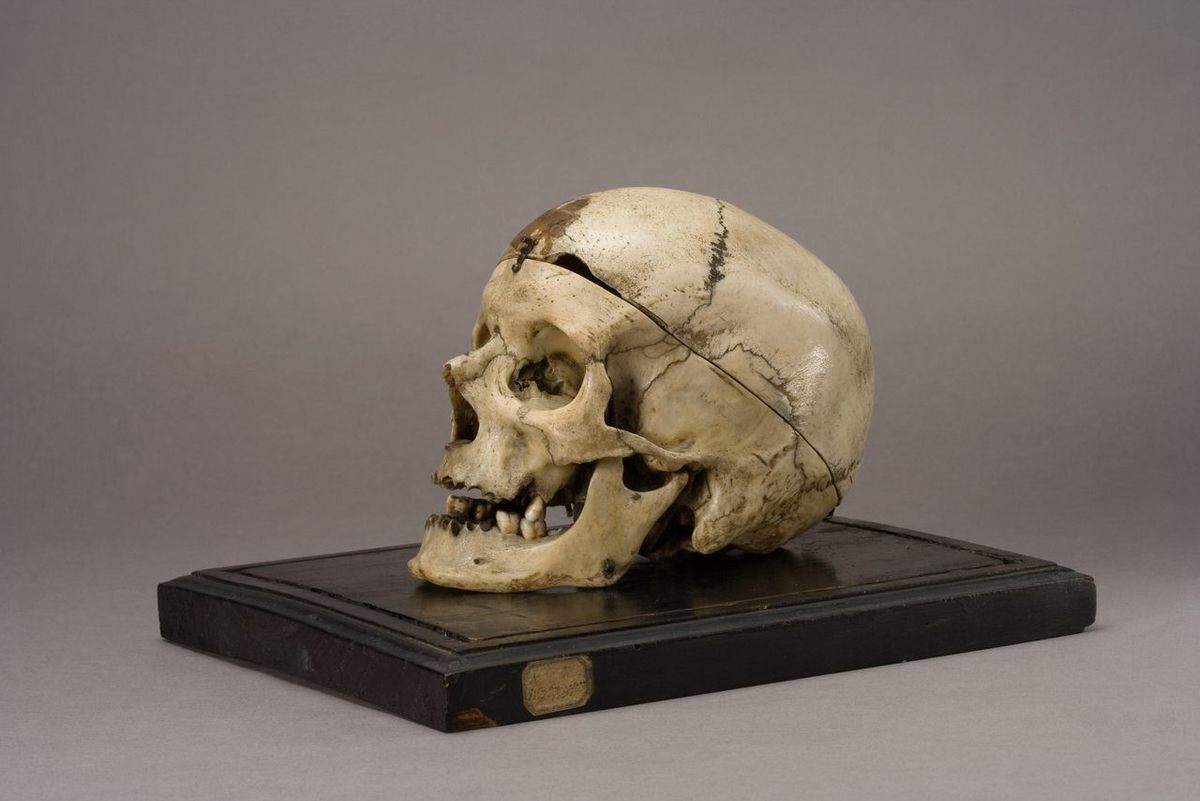

Why Is Everyone Fighting Over the Skull of ‘Brigand Villella’?

by Dania Rodrigues

In December 1870, Cesare Lombroso, a prominent Italian scientist, declared the skull of “Brigand Villella” was evidence that a physical trait was connected with deviant behavior. Lombroso’s theories have long since been debunked as dangerous pseudoscience, but Giuseppe Villella’s skull—and the facts of his life—have become an issue in modern-day Italian politics. Was Villella a patriot, as Southern Italian parties have declared, or a criminal, as Lombroso believed? The truth is that he was neither, writes Dania Rodrigues. “The real history is actually much more fascinating than the fiction,” says anthropologist Maria Teresa Milicia who uncovered his story. “Giuseppe Villella was not a hero or a villain, but a victim of the brutality of his times.”

Seeking the Last Remnants of South Dakota’s ‘Divorce Colony’

by April White, Senior Writer/Editor

April White visited Sioux Falls, South Dakota, to research her new book, The Divorce Colony: How Women Revolutionized Marriage and Found Freedom on the American Frontier. She found the evidence that remains from the time when the city was home to scores of unhappy spouses, many of whom had traveled more than a thousand miles to end their marriages. These remnants of what scandalized 19th-century journalists came to call the “divorce colony” tell the overlooked story of the evolution of marriage—and its end—in the United States.

What We Overlooked in King Tut’s Tomb

by Amy Crawford

The discovery made front-page news around the world: In November 1922, noted English archaeologist Howard Carter unearthed the long-sought tomb of the Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun, apparently undisturbed in the more than 32 centuries since the king’s untimely death at 19 years old. But what was missing from those stories, reports Amy Crawford, was a true understanding of the role modern-day Egyptians had in uncovering their country’s history. A new exhibition at the Oxford’s Bodleian Libraries, Tutankhamun: Excavating the Archive, which runs through February 2023, puts Egyptians back into the story.

The Forgotten Women Who Ruled the Medieval Middle East

by Sarah Durn, Associate Editor

Katherine Pangonis’s 2022 book, Queens of Jerusalem: The Women Who Dared to Rule, explores the complicated lives and legacy of the forgotten women who ruled the medieval Middle East. Sarah Durn interviewed Pangonis for Atlas Obscura’s Q&A series She Was There, conversations with female scholars who are writing long-forgotten women back into history. Why have these women been overlooked? “Because the chronicles are written by men,” Pangonis says.

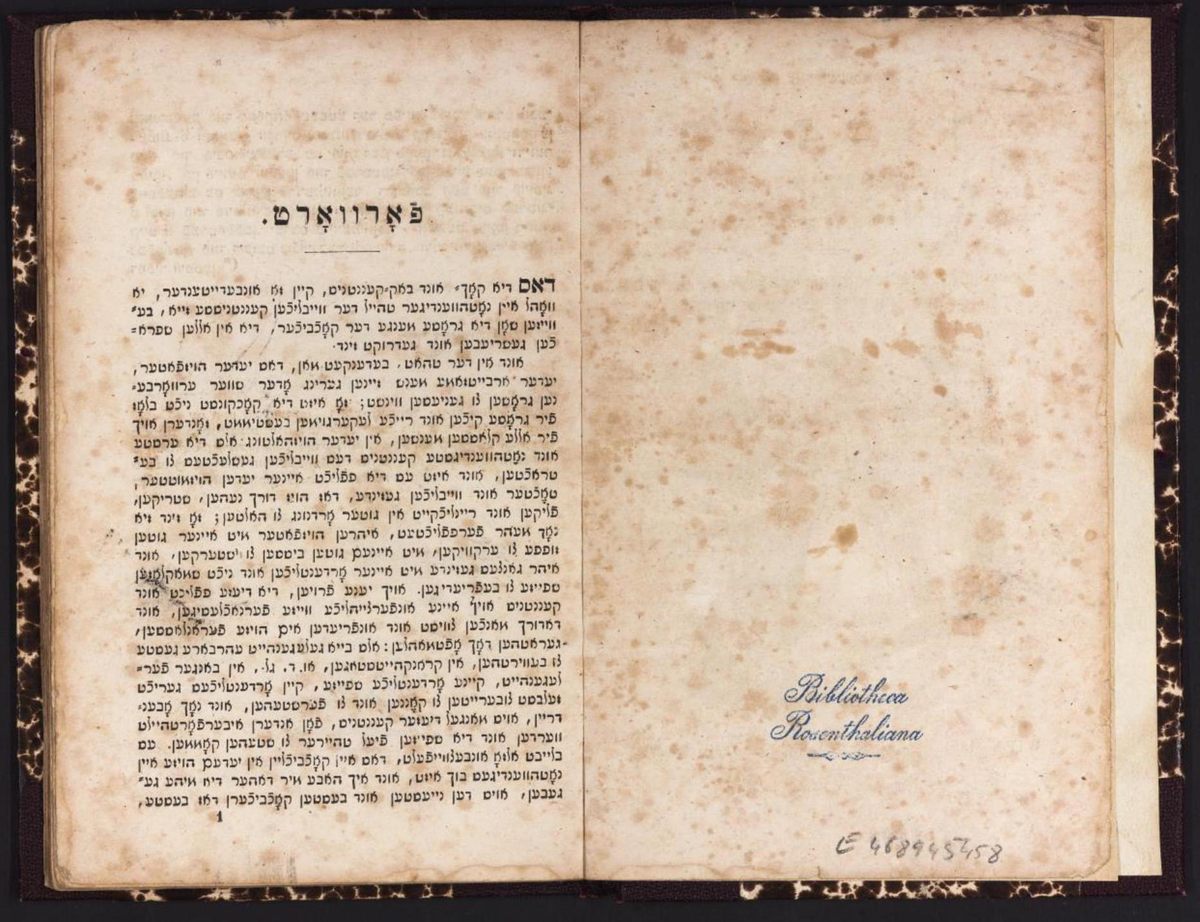

One Man’s Search for the First Hebrew-Lettered Cookbook

by Sam Lin-Sommer, Editorial Fellow, Gastro Obscura

András Koerner, the foremost expert on Hungarian Jewish culinary history, thought that the oldest-known Hebrew-lettered cookbook had been destroyed. But this year he finally got to see the treasure he had been chasing at the Hungarian Museum of Trade and Tourism, reports Sam Lin-Sommer. This collection of recipes, published in 1854 in Budapest, was 40 years older and of a completely different national origin than the book that historians had previously regarded as the first Hebrew-lettered cookbook. “I don’t want to exaggerate it, but at least within scholarly circles, it was a small sensation,” says Koerner.

How a Farmer’s Hunch Led to a Lost Monastery and a Neolithic Surprise

by Matt McIntosh

John McCullen had long believed that the old stone tower on his family farm north of Dublin was a historic site. His hunch proved correct, reports Matt McIntosh. The tower was the only remaining building from a lost medieval monastery. Even more surprising: Beneath the tower and other remains of the medieval site are much older structures, which date back millennia. The complex, archaeologists say, is unique in all of Ireland.

Is the Silence of the Great Plains to Blame for ‘Prairie Madness’?

by James Gaines

In the 1880s, as American settlers pushed into the Great Plains, stories began to emerge of formerly stable people becoming depressed, anxious, irritable, and even violent—with “prairie madness.” And there is some evidence in historical accounts or surveys, which suggested a rise in cases of mental illness in the mid-1800s to early 1900s, particularly in the Great Plains. Both fictional and historical accounts of this time and place often blame “prairie madness” on the isolation and bleak conditions the settlers encountered. But many also mention something unexpected: the sound. James Gaines reports that a new study suggests that these writers might have been on to something. The peculiar soundscape of the prairies could have affected the minds of the settlers.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook