The Long, Extremely Witchy History of Telling the Future With Eggs

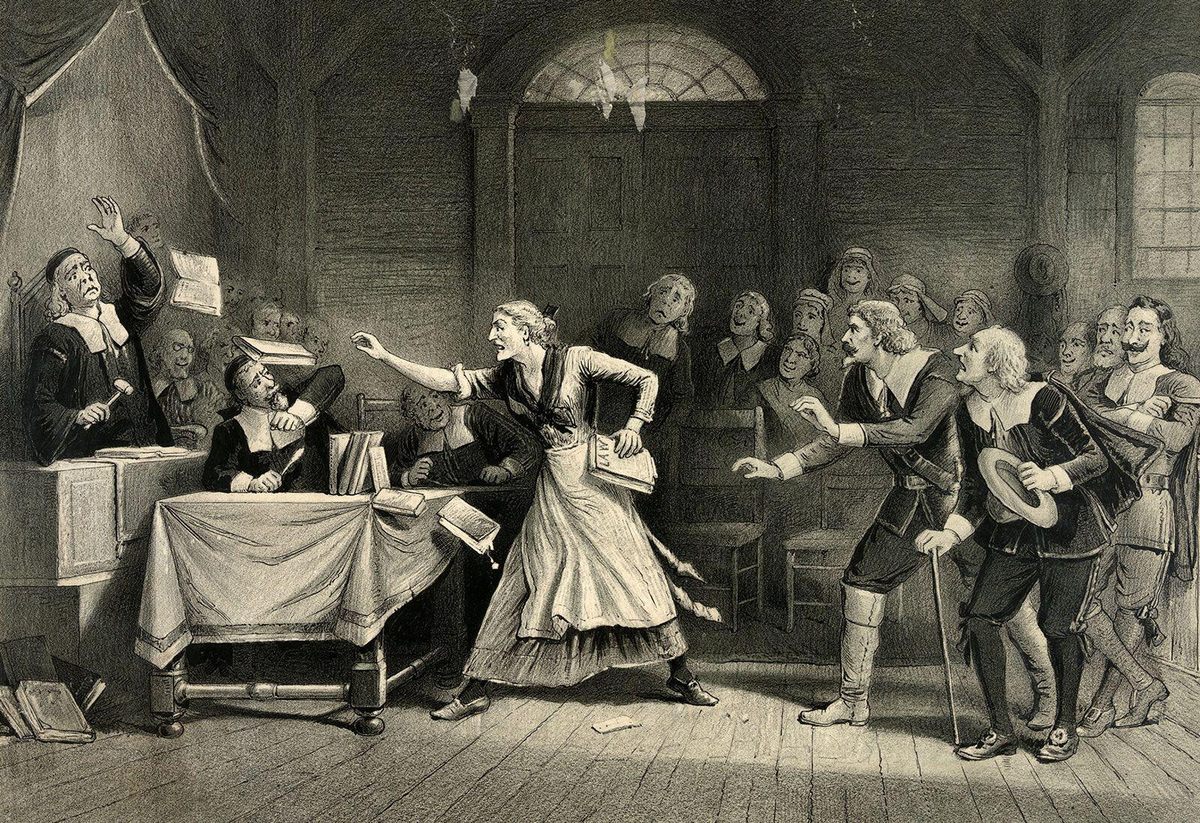

From ancient Greece to the Salem Witch Trials.

Shortly before his death in 1700, John Hale, a Puritan reverend from Beverly, Massachusetts, decided to document a dark historical moment. His posthumously published work, A Modest Inquiry Into the Nature of Witchcraft, is one of the few written records from someone present at the Salem Witch Trials.

Whether or not Hale is a reliable narrator, he certainly had the credentials to write such a text. At the age of 12, he saw his first execution of a convicted “witch.” As an adult, Hale was a pivotal figure in the Salem Witch Trials themselves. From 1692 to 1693 the accusations of witchcraft mounted to more than 200. Hale, as a reverend, was present to listen to confessions. In the process, he also testified against two of his parishioners: Sarah Bishop, often referred to as “Goody Bishop, wife of Edward Bishop,” and Dorcas Hoar, a fortune-teller.

Hale later came to regret much of the proceedings—conveniently, after someone accused his wife of witchcraft. Yet he still vehemently condemned the practice of witchcraft until his deathbed. “In the 1600s, the Puritan hierarchy was very opposed to magic of any form—particularly fortune-telling,” says Peter Muise, author of Witches and Warlocks of Massachusetts. But that didn’t stop people in New England from practicing it anyway.

Hale’s accounts described one particularly interesting form of divination: oomancy, or using eggs to interpret the future. Even by the 17th century, the idea of oomancy was already age-old. Ancient Greek soothsayers coined the term, which stems from the words for “egg” (oon) and “divination” (manteia). Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, a Roman historian who lived from 69 to 122 B.C., once described how the Empress Livia Drusilla kept a chicken egg in her cleavage believing that its sex would foretell the sex of her unborn child.

Cultures around the world, from Southeast Asia to Latin America, have relied on eggs to unscramble the mysteries of the future. One method, described by Hale as the “Venus glass,” may have its roots in Scotland. The concept is simple: take a glass of warm water, slowly pour in a raw egg white, and watch what shapes form as the proteins denature. Much like tea leaf-reading, or tasseomancy, the resulting shapes offer clues as to whom you might marry or how you might die.

“If you see that the egg whites kind of look like a plow or a horse, your husband might be a farmer,” Muise explains. “Or if it looks like a fortress, your husband might be a soldier, or if it looks like a boat, your husband might be a fisherman.”

For the ancient Druids, oomancy was often an important part of the celebrations for Samhain, the pagan holiday from which most Halloween traditions originated. German pagans used a similar fortune-telling technique with egg whites in water, which they sometimes referred to as Eierorakel, or an “egg oracle.” In his 1878 book Deutschen Mythologie, Jakob Grimm describes tossing an egg in water to find out if a child was bewitched.

Part of its widespread appeal may lie in the egg’s inherent connection to birth and the cycle of life; a greater part has to do simply with its near-universal accessibility. “[Puritans] didn’t have a lot of material stuff,” Muise says. “You see magic with apples, eggs, cabbage, nuts, because that’s what people had around the house. They didn’t have tarot cards or crystals.”

Perhaps in part because making a “Venus Glass” was so easy, Puritan ministers railed against the practice. Yet human beings have always been curious about what lies in store, particularly in uncertain times. At the start of the Salem Witch Trials, New England was in a state of political and social unrest. Refugees were pouring in from other parts of the colonies, thanks to King William’s War with the French, and Salem Town, a prosperous harbor made wealthy from trade, was on the verge of separating from Salem Village, a relatively poor farming community.

People wanted answers in this unstable climate, and were willing to ignore the local reverend to get them. “If you’re a captain trying to figure out when to set sail for your next voyage, you might consult an astrologer,” Muise says. “And certainly for single people, particularly women, they would often do magic to find out who they would marry.”

In Hale’s account of witchcraft in Massachusetts, two women confessed to playing with the “Venus glass,” but instead of seeing a plow or a boat, saw a coffin. He claims both suffered from “diabolical molestations” and that one died shortly thereafter.

It’s not a coincidence that food-centric magic features so prominently in the lore of the witch trials. Tales of witches from the 1600s often fixate on their culinary elements. “The butter won’t churn, because a witch has bewitched the cream itself,” Muise says. “They may make food spoil, they may make a cow give rotten milk out of its udders. So often the witch is very much imagined to be disrupting the domestic production of food.”

At the time, women were responsible for virtually all food production, from the beer that kept the Puritans hydrated in the absence of sanitary water, to the bread on their tables. Any woman who dared to disrupt her domestic lot in life, was a threat to the social hierarchy and stability of these small, fragile societies. It’s little wonder that many of the women accused of black magic in Salem were those who lived somewhat outside the social norms; or that their supposed transgressions often started in the kitchen.

As the mass hysteria around witches began to fade, so did the moral panic around fortune-telling. Food-centric methods of fortune-telling, from oomancy to dumb cakes, which the Puritans had regarded as dangerous entry points to Devil worship, were increasingly regarded as harmless party games. While the “Venus glass” may have fallen out of fashion, there’s nothing to stop modern-day Halloween celebrants from attempting to decipher their future in a swirling mass of egg whites.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook